Date: September 9, 2025

Part 13: The Yoga of the Renunciation of Action – 3

Continued from Part 12

Karmayoga and Equality

The Gita attaches immense importance in its elements of Karmayoga to equality; “it is the nodus of the free spirit’s free relations with the world,” says Sri Aurobindo. For one who is always withdrawn into oneself, self-absorbed in his desirelessness, impersonality and freedom from the modes of Prakriti, there is no need of equality. But the moment one comes in contact with the multiplicity of the outer life and world, equality becomes the paramount sign. If the liberated soul is to “allow its nature any action at all, it must show its superiority by an impartial equality towards all activities, results or happenings” (Sri Aurobindo, CWSA, Vol. 19, p. 189).

In the absence of equality in the soul, one is always prone to the play of the modes of Nature, movement of desire, personal will, feeling and action. Also there will be ups and downs of joy and grief or “that disturbed and disturbing delight which is not true spiritual bliss but a mental satisfaction bringing in its train inevitably a counterpart or recoil of mental dissatisfaction”. Only by his equality the Karmayogin while being in the midst of action remains free.

The Gita speaks of three ways to attain this equality which leads to divine peace: heroic endurance or titikṣā, sage indifference or udāsīnatā, and pious resignation or namas or nati. But it insists that these are not the qualities of the mind (as in the case of a philosopher) or the character (as in the case of a saint). The Gita gives to each of these a profounder root, a more universal and transcendent significance. “For to each it gives the values of the spirit, its power of spiritual being beyond the strain of character, beyond the difficult poise of the understanding, beyond the stress of the emotions.” (ibid., p. 190)

Sri Aurobindo explains further,

The philosopher maintains his equality by the power of the buddhi, the discerning mind; but even that by itself is a doubtful foundation. For, though master of himself on the whole by a constant attention or an acquired habit of mind, in reality he is not free from his lower nature, and it does actually assert itself in many ways and may at any moment take a violent revenge for its rejection and suppression.

For, always, the play of the lower nature is a triple play, and the rajasic and tamasic qualities are ever lying in wait for the sattwic man. “Even the mind of the wise man who labours for perfection is carried away by the vehement insistence of the senses.” Perfect security can only be had by resorting to something higher than the sattwic quality, something higher than the discerning mind, to the Self,—not the philosopher’s intelligent self, but the divine sage’s spiritual self which is beyond the three gunas. All must be consummated by a divine birth into the higher spiritual nature.

~ CWSA, Vol. 19, pp. 198-199

The Gita proclaims that as long as we are bewildered by Ignorance, the Avidya, and do not have the eternal knowledge of the secret Brahman within our being, we can not attain this “perfect security”. But attaining this knowledge is not an intellectual activity of the mind, Sri Aurobindo clarifies, “it is a luminous growth into the highest state of being by the outshining of the light of the divine sun of Truth” (ibid., p. 201).

By turning our discerning mind to the Supreme, directing our whole conscious being to That, making That the whole aim and the sole object of our devotion, we become one thought and self with That. We reach the abode from where there is no return to the cycle of birth and death, and all the darkness and suffering of our lower nature is washed clean by the waters of knowledge.

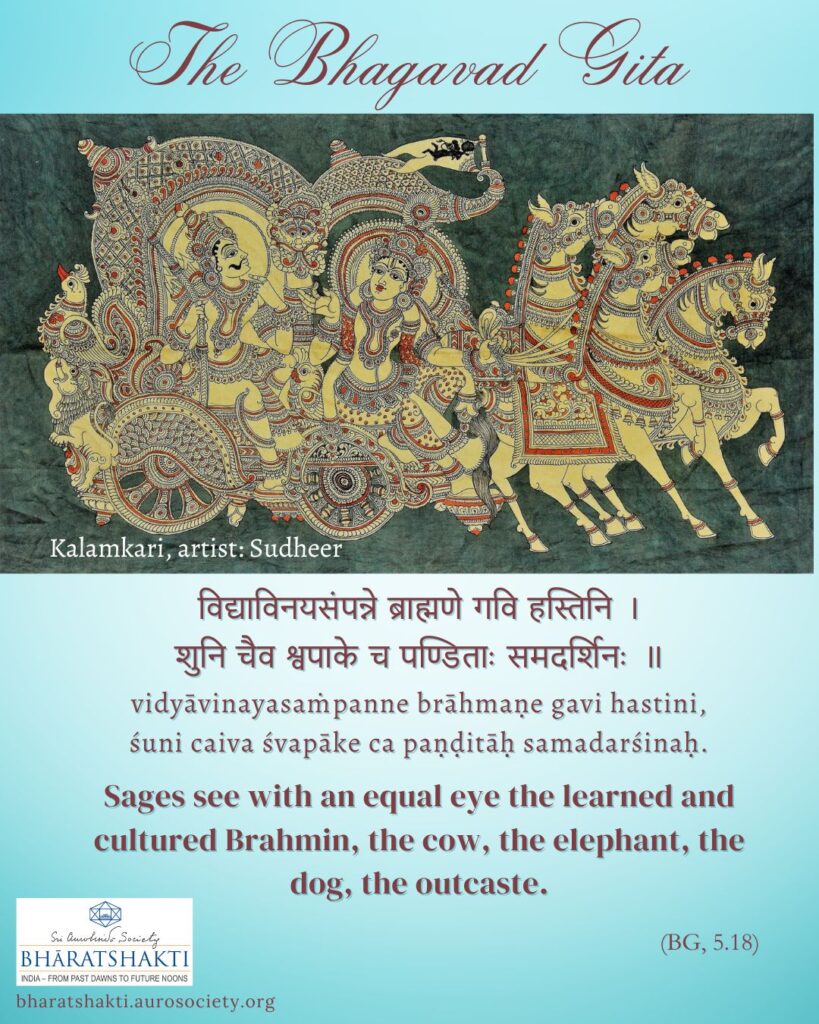

Sages with this eternal knowledge develop a perfect equality to all things and all persons. They see with an equal eye the learned and cultured Brahmin, the cow, the elephant, the dog, the outcaste, and know all as one Brahman. Living in this oneness they become free from all attachment or bondage and see their works proceeding freely from the nature. With mind established in equality they live in the supreme and divine Nature; for them there is no longer any fault or defect, sin or stain in their works because they know that these too are created by the inequalities of the ignorance. “The equal Brahman is faultless, beyond the confusion of good and evil, and living in the Brahman we too rise beyond good and evil;…” (pp. 202-03).

Sri Krishna adds that one with stable intellect, un-bewildered by ignorance, knower of the Brahman and living in the Brahman, neither rejoices on obtaining what is pleasant nor sorrows on obtaining what is unpleasant. Unattached to the touches of outward things one finds happiness that exists in the Self. United with the Brahman, such Yogin enjoys an imperishable happiness. One with this inner happiness, inner ease and repose, and the inner light becomes the Brahman and reaches self-extinction in the Brahman, brahmanirvānam.

Perfect Spiritual Freedom

True happiness is only possible with a non-attachment and with freedom from the attacks of desire, wrath and passion. A perfect spiritual freedom is to be won here upon earth and possessed and enjoyed in the human life, says Sri Aurobindo.

“That happiness and that equality are to be gained entirely by man in the body: he is not to suffer any least remnant of the subjection to the troubled lower nature to remain in the idea that the perfect release will come by a putting off of the body…” (p. 236).

Further clarifying the sense in which the Gita uses the word Nirvana, Sri Aurobindo explains that Nirvana here means “the extinction of the ego in the higher spiritual, inner Self, that which is for ever timeless, spaceless, not bound by the chain of cause and effect and the changes of the world-mutation, self-blissful, self-illumined and for ever at peace.

The Yogin ceases to be the ego, the little person limited by the mind and the body; he becomes the Brahman; he is unified in consciousness with the immutable divinity of the eternal Self which is immanent in his natural being.” (p. 236). Such sages who are masters of their selves, are in a state of Nirvana in the Brahman, and in whom the stains of sin are effaced are always engaged with a large sense of equality in doing good to all creatures.

This chapter concludes by reiterating one of the great ideas of the Gita, the idea of the Purushottama, when Sri Krishna says: “When a man has known Me as the Enjoyer of sacrifice and tapasya, the mighty lord of all the worlds, the friend of all creatures, he comes by the peace.” Whenever Sri Krishna speaks of “I” or “Me”, he is speaking of and as Purshottama, who is described by Sri Aurobindo as:

“…the Divine who is there as the one self in our timeless immutable being, who is present too in the world, in all existences, in all activities, the master of the silence and the peace, the master of the power and the action, who is here incarnate as the divine charioteer of the stupendous conflict, the Transcendent, the Self, the All, the master of every individual being.

“He is the enjoyer of all sacrifice and of all tapasya, therefore shall the seeker of liberation do works as a sacrifice and as a tapasya; he is the lord of all the worlds, manifested in Nature and in these beings, therefore shall the liberated man still do works for the right government and leading on of the peoples in these worlds, loka-saṅgraha; he is the friend of all existences, therefore is the sage who has found Nirvana within him and all around, still and always occupied with the good of all creatures.” (p. 239).

To be continued…